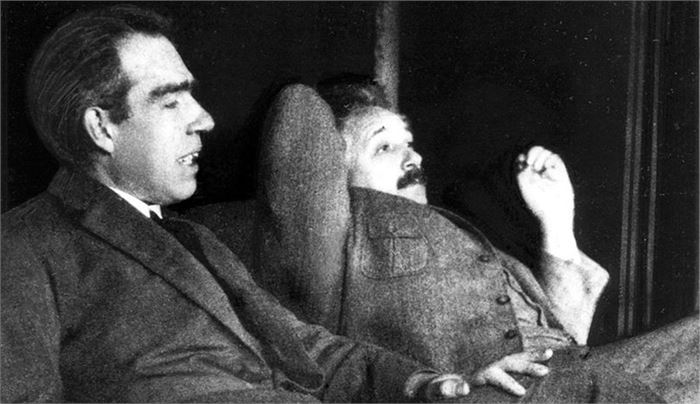

토론하는 보어와 아인슈타인. 1925년 12월 스위스 라이덴의 폴 에렌페스트 집. Niels Bohr (left) with Albert Einstein (right) at Paul Ehrenfest's home in Leiden (December 1925)

토론하는 보어와 아인슈타인. 1925년 12월 스위스 라이덴의 폴 에렌페스트 집. Niels Bohr (left) with Albert Einstein (right) at Paul Ehrenfest's home in Leiden (December 1925)

보어-아인슈타인 논쟁 – 1 : 변형 이중슬릿 사고실험

닐스 보어는 1927년 9월 이탈리아 코모 호수가에서 열린 물리학회에서 코펜하겐 해석을 공식 제안한 데 이어 한 달 뒤 당대 최고의 물리학술대회인 솔베이회의의 제5차 대회에서 코펜하겐 해석을 받아들이도록 물리학자들을 설득하는 데 성공했다. 그는 물리학자들을 일일이 찾아다니며 코펜하겐 해석의 논리를 끈질기게 설명하고 납득시켰다. 보어는 물리학자들을 붙잡고 ‘한 마디만 하자’며 새벽까지 열변을 토하는 게 보통이었다.

그러나 양자론의 기초를 다졌던 아인슈타인과 슈뢰딩거 등 일부 물리학자들은 양자론을 강력하면서도 끈질기게 비판했다. 양자론 공격의 선봉장은 아인슈타인이었다. 그는 타계할 때까지 ‘양자론의 불완정성’을 주장했다.

그런데 아인슈타인은 1905년 광양자 가설을 발표해 양자역학의 태동에 기여한 인물이다. 그렇다면 왜 아인슈타인은 그토록 양자역학을 반대했을까?

그것은 아인슈타인이 양자론의 철학적 의미를 받아들일 수 없었기 때문이다. 구체적으로 말하면 양자역학이 내포하고 있는 비결정론(확률해석)과 비실재성 그리고 특수상대성이론의 기본 원리와 상충하는 듯 보이는 비국소성 때문이다.

아인슈타인은 1927년 제5차 솔베이회의와 1930년 제6차 솔베이회의에서 공식적으로 양자역학의 불완전성을 지적하는 사고실험을 제기해 보어를 곤경에 빠뜨리는 듯했으나 성공하지는 못했다.

그리고 1935년 아인슈타인은 포돌스키, 로젠과 함께 쓴 논문 「물리적 실재에 대한 양자역학적 기술은 완전한가?(Can Quantum Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?)」라는 제목의 논문을 권위 있는 물리학 잡지 ‘Physical Review’ 47호에 게재했다. 이것이 아인슈타인 팀과 양자론 학자들과의 반세기 동안 논쟁을 야기한 그 유명한 ‘EPR 논증’이다.

이 논증은 공동발표자인 Einstein과 그의 공동연구자 및 제자인 Boris Podolsky, Nathan Rosen의 이름 첫 글자를 따 EPR 논증이라고 불린다. 양자역학의 불완전성을 공격한 이 논증은 아이러니컬하게도 양자역학을 확증해주는 데 크게 기여했다. 이제부터 세기의 천재인 아인슈타인이 양자론을 놓고 보어와 벌인 50년에 걸친 논쟁을 차례로 알아보겠다.

변형 이중슬릿 사고실험을 통한 불확정성 원리 공격

아인슈타인은 몇 년에 걸친 노력 끝에 양자역학의 구조적 결함을 지적하는 매우 정교한 논리를 완성시켰다. 직접적인 공격 대상은 불확정성 원리였다. 1927년 브뤼셀에서 개최된 제5차 솔베이회의에서 아인슈타인은 다음과 같은 이중슬릿 사고실험(thought-experiment)을 제시하였다.

아인슈타인의 공격

아인슈타인은 상보적인 두 물리량을 동시에 관측할 수 없을 뿐 아니라 이들 입자가 이들 물리량을 확정적인 속성으로 갖고 있다고 생각해서는 안 된다는 보어의 주장을 반박하고자 했다.

이를테면 아인슈타인은 이중슬릿 실험의 경우 간섭무늬를 볼 수 있다면 그 상보적인 양인 입자의 경로를 알 수 없다는 보어의 주장에 동의할 수 없었다. 그래서 아인슈타인은 보어의 주장을 근본적으로 뒤엎으려고 시도했다. 아인슈타인의 목표는 이 실험을 통해 서로 상보적인 두 물리량을 동시에 관찰하는 것이 가능함을 보이는 것이었다. 그는 매우 기발한 사고실험을 고안했다.

스프링이 달린 입구 판을 추가한 변형 이중슬릿 사고실험 개요도. 1927년 아인슈타인이 제기한 문제를 풀기 위해 보어가 그렸다.

아인슈타인은 보통 이중슬릿 실험 장치를 정교하게 변형했다. 그는 모든 입자들의 경로를 결정할 수 있으면서 간섭무늬도 만드는 장치라고 확신했다. 그는 입구 슬릿이 고정되지 않도록 고안했다. 입구 슬릿 판을 나머지 부분에 나사로 조이지 않고 자유롭게 움직일 수 있도록 설계한 것이다.

아인슈타인은 단 한 개의 입자가 장치를 통과하도록 제어하면서 개별 입자로 이 실험을 수행할 수 있다고 주장했다. 한 입자를 보내기 전에 입구 판이 흔들리지 않도록 만든다. 이어서 입자를 보내고, 스크린의 어느 위치에 입자가 도착하는지 기록한다. 당연한 일이지만 입구 판의 슬릿을 통과한 입자가 이중슬릿 판의 다른 두 슬릿을 항상 통과하는 것은 아니다. 우리는 다만, 스크린까지 도달한 입자들만 관찰한다.

관찰 영역에서 입자가 기록되었다면 그 입자는, 아인슈타인의 견해에 따르면, 두 슬릿 중 하나를 거쳤음에 틀림없다. 그러므로 입자가 처음에 전체 장치의 기판에 평행하게 들어왔다면 그 입자는 입구 판의 슬릿에서 위로 혹은 아래로 굴절되어야 한다. 그러므로 입자의 운동량은 변해야 하며 입구 판은 충격을 받고 움직여야 한다.

입자가 위 슬릿을 통과한다면 입구 판은 아래로 충격을 받아야 한다. 이때 우리는 첫 번째 입자가 입구 슬릿을 통과하고 스크린에 기록된 후에 입구 판이 위로 움직였는지, 혹은 아래로 움직였는지 관찰한다. 따라서 이를 통해 우리는 입자가 어느 경로를 택했는지 확실히 할 수 있다는 것이 아인슈타인의 주장이다.

우리는 입자가 도달한 스크린 상의 위치를 이미 측정했다. 이어서 입구 판을 다시 처음대로 흔들리지 않게 놓고 다른 입자로 실험을 반복한다. 이런 방식으로 점차 많은 입자들이 스크린에 도달할 것이고, 아인슈타인에 따르면 스크린에는 점차 간섭무늬가 형성될 것이다. 동시에 우리는 모든 각각의 입자가 어느 경로를 거쳤는지 말해주는 목록을 가지게 될 것이다.

이 사고실험을 통해 아인슈타인은 ‘입자의 경로를 파악하면 간섭무늬가 생기지 않고, 입자의 경로를 모르면 간섭무늬가 생긴다’는 불확정성 원리가 오류임을 간단명료하게 논증했다고 자신했다.

언뜻 보기에 이 논증은 전적으로 합리적이고 적합해 보인다. 만일 이 논증이 옳다면 양자역학의 토대인 불확정성 원리는 오류임이 판명되는 것이며, 나아가 그 토대 위에 세워진 양자역학과 코펜하겐해석은 폐기되어야 할 운명에 처해진 것이다.

보어의 방어

보어는 아인슈타인의 논증을 면밀히 분석한 끝에 결정적인 오류를 발견했다. 아인슈타인이 사고실험 장치에서 스프링이 달린 입구 판을 정확히 멈추어 있도록 만들 수 있다고 전제한 바로 그 점이다.

그러나 이것은 양자역학, 구체적으로 불확정성 원리가 불허하는 두 가지 상태를 요구하는 것이다. 즉, 아인슈타인은 입구 판이 멈추어 있으면서, 즉 속도가 0이면서 동시에 정확히 고정된 위치에 있을 수 있다고 전제한 것이다. 이는 위치 불확정성과 운동량 불확정성이 동시에 0일 것을 요구한다.

그러나 하이젠베르크의 불확정성 원리가 주장하듯이 양자역학에 따르면 그것은 근본적으로 불가능하다. 아인슈타인이 범한, 또한 오늘날에도 사람들이 매우 흔히 범하는 오류는 양자역학의 법칙들이 입구 판에도 적용되어야 한다는 것을 간과한 것이다.

아인슈타인이 제안한 사고실험의 목표는 입구 판이 흔들리는 것을 보고 입자가 위로, 혹은 아래로 굴절되었다는 것을 추론하는 것이다. 하지만 입구 판이 불확정성 원리에 의해 ‘완전히 정지’ 상태에 있게 만들 수 없기 때문에, 입구 판의 흔들림으로부터 입자의 굴절된 방향의 추론은 타당성을 담보할 수 없게 되는 것이다.

흥미롭게도 보어는 아인슈타인이 불확정성을 공격한 이 사고실험에서 상보성 원리가 정확하게 성립한다는 사실을 증명했다. 입자가 택하는 경로를 우리가 정확히 알면 간섭무늬는 완전히 사라진다. 우리가 선명한 간섭무늬를 얻으면, 입자의 경로에 대해서는 아무 말도 할 수 없게 된다.

아인슈타인은 보어의 논증을 수용할 수밖에 없었다. 보어는 아인슈타인의 공격을 완벽하게 막아내며 이 논쟁에서 확실히 승리했다. 그러나 양자역학의 불완전성을 확신하고 있던 아인슈타인은 완전히 승복한 것은 아니었다. 1차전 패배가 확실해진 그 순간부터 2차 전투를 준비했던 것이다. 자신의 논증을 더욱 개량하여 더 복잡하고 정교한 사고실험 고안에 착수했다.

The Bohr-Einstein Debate 1 : A modified Double-Slit Thought Experiment

Niels Bohr officially proposed the Copenhagen Interpretation at the Como Conference held on the shores of Lake Como, Italy in September 1927, and a month later, at the 5th Congress of the Solvay Conference, the greatest physics conference of the time, Niels Bohr was succeeded in persuading physicists to accept the Copenhagen Interpretation.

He visited physicists one by one and persistently explained and convinced them of the logic of the Copenhagen Interpretation. It was common for Bohr to hold on to physicists and say, “Let’s just say one word,” and persuade until dawn.

However, some physicists such as Einstein and Schrödinger, who laid the foundations of quantum theory, strongly and persistently criticized quantum theory. The vanguard of the attack on quantum theory was Einstein. He insisted on 'incompleteness of quantum theory' until his death.

By the way, Einstein contributed to the birth of quantum mechanics by announcing the light-quantum hypothesis in 1905. So why was Einstein so opposed to quantum mechanics?

It is because Einstein could not accept the philosophical meaning of quantum theory. Specifically, it is because of the non-determinism (probability interpretation) and non-reality of quantum mechanics, and the non-locality that seems to conflict with the basic principle of special relativity.

At the 5th Solvay Conference in 1927 and the 6th Solvay Conference in 1930, Einstein formally proposed a thought experiment pointing out the incompleteness of quantum mechanics, which seemed to get Bohr into trouble, but he did not succeed.

And in 1935, Einstein published a paper titled 「Can Quantum Mechanical Description of Physical Reality be Considered Complete?」, written with Podolsky and Rosen, in the 47th issue of the prestigious physics magazine Physical Review. This is the famous 'EPR argument' that has sparked debate between Einstein's team and quantum scholars for half a century.

This argument is called the EPR argument after the first letters of the names of co-presenter Einstein and his co-researchers and students Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen. This argument, which attacked the incompleteness of quantum mechanics, ironically contributed greatly to confirming quantum mechanics. From now on, we will look at the 50-year-long debate that Einstein, the genius of the century, had with Bohr over quantum theory in turn.

Attacking the uncertainty principle through a modified double-slit thought experiment

After years of effort, Einstein has perfected a very sophisticated logic that points out the structural flaws in quantum mechanics. The direct target of the attack was the uncertainty principle. At the 5th Solvay Conference held in Brussels in 1927, Einstein presented the following modified double-slit thought experiment.

Einstein's argument

Einstein tried to refute Bohr's assertion that not only can two complementary physical quantities not be simultaneously observed, but that these particles should not be considered to have these physical quantities as deterministic properties.

For example, Einstein could not agree with Bohr's claim that in the case of the double-slit experiment, if one could see the interference pattern, one could not know the path of the particle, the complementary quantity. So Einstein attempted to fundamentally reverse Bohr's argument. Einstein's goal was to show through his thought experiment that it is possible to simultaneously observe two complementary physical quantities. He devised a very ingenious thought experiment.

Schematic diagram of a modified double-slit thought experiment with the addition of a spring-loaded entry plate. It was drawn by Bohr in 1927 to solve a problem posed by Einstein.

Einstein made elaborate modifications to the usual double-slit experimental setup. He was convinced that it was a device that could determine the path of all particles and also create interference patterns. He designed the entrance slit not to be fixed. He designed the entry slit plate to move freely without screwing it to the rest.

Einstein claimed that he could do this experiment with individual particles, controlling only one particle to pass through the device. Make the inlet plate steady before sending one particle. Then send the particles and record where they land on the screen. Naturally, particles passing through the slits in the inlet plate do not always pass through the other two slits in the double-slit plate. We only observe particles that reach the screen.

If a particle was recorded in the field of observation, it must have, in Einstein's opinion, passed through one of the two slits. Therefore, if a particle initially enters parallel to the substrate of the entire device, it must be deflected up or down at the slit in the inlet plate. Thus, the particle's momentum must change and the inlet plate must be shocked and moved.

If a particle passes through the upper slit, the inlet plate must be impacted downward. Here we observe whether the entrance plate moved up or down after the first particle passed through the entrance slit and was recorded on the screen. So, Einstein argued, this allows us to be sure which path the particle took.

We have already measured the position on the screen that the particle has reached. The inlet plate is then placed back to the original position and the experiment is repeated with other particles. In this way, more and more particles will reach the screen, which, according to Einstein, will gradually form an interference fringe. At the same time we will have a list that tells which path every single particle has taken.

Through this thought experiment, Einstein was confident that he had simply and concisely argued that the uncertainty principle, which states that "if the path of a particle is known, no interference pattern is formed, and if the path of a particle is not known, an interference pattern is created" is false.

At first glance, this argument seems entirely reasonable and fitting. If this argument is correct, the uncertainty principle, the foundation of quantum mechanics, is proven to be erroneous, and furthermore, quantum mechanics and the Copenhagen interpretation built on that foundation are doomed to be discarded.

Bohr’s response

After careful analysis of Einstein's argument, Bohr discovered a crucial fallacy. That's exactly what Einstein assumed in his thought experiment that he could make the spring-loaded entrance plate stay exactly at rest.

However, this requires two states that quantum mechanics, specifically the uncertainty principle, does not allow. In other words, Einstein assumed that the inlet plate could be stationary, i.e., with zero velocity and at the same time in a precisely fixed position. This requires that the position uncertainty and momentum uncertainty be zero at the same time.

But according to quantum mechanics, as Heisenberg's uncertainty principle claims, that's fundamentally impossible. A mistake Einstein made, and still very common today, is to overlook that the laws of quantum mechanics should apply to the inlet plate as well.

The goal of Einstein's thought experiment is to infer that the particle is deflected up or down by seeing the swinging of the entrance plate. However, since the inlet plate cannot be made to be 'completely stationary' by the uncertainty principle, the inference of the refracted direction of the particle from the shaking of the inlet plate cannot be validated.

Interestingly, in this thought experiment in which Einstein attacked uncertainty, Bohr proved that the principle of complementarity holds precisely. If we know exactly which path the particle takes, the interference pattern disappears completely. If we get sharp interference fringes, we can't say anything about the particle's path.

Einstein had no choice but to accept Bohr's argument. Bohr won the debate convincingly, completely blocking Einstein's attack. However, Einstein, who was convinced of the incompleteness of quantum mechanics, did not completely surrender. From the moment he was sure to lose the first match, he prepared for the second fight. He further refined his own arguments and set about designing more complex and sophisticated thought experiments.

<pinepines@injurytime.kr>